|

China’s Shrinking Cities Are Still Addicted to Building

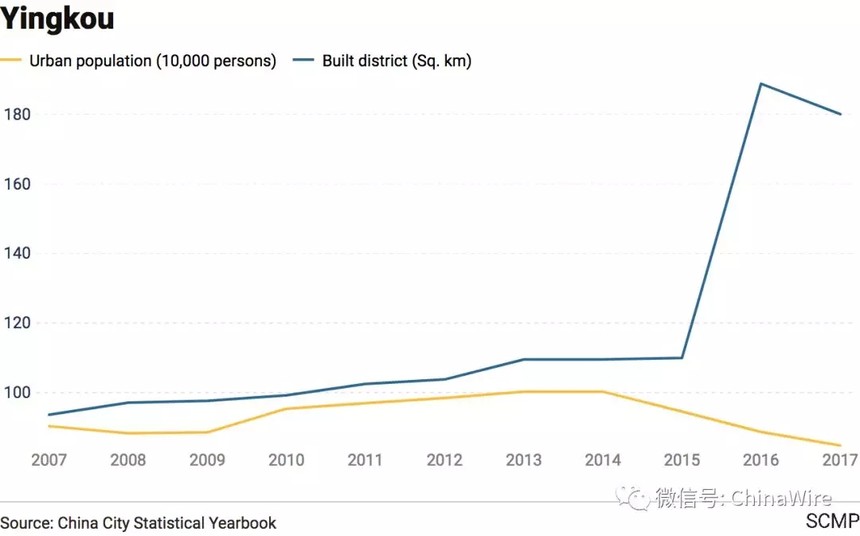

Dozens of cities in China are spending big on construction projects, despite having shrinking populations, a South China Morning Post analysis has found. On paper, these debt-fuelled projects are major contributors to economic growth, but in reality, they do not bring real productivity, raising further questions about the efficiency and foresight of China’s urban planning. New urban constructions should, in theory, go hand in hand with population growth, but in many shrinking cities, local governments are still building, even though they need to accommodate fewer people. The Post analysed official population statistics for the 661 officially-designated cities in China between 2010 and 2017. After discounting those that had either been absorbed into other urban sprawls or did not exist in 2010, 627 remained. Of these, the population declined in 90, or 14 per cent of all Chinese cities. Over the same period, 71 of those shrinking cities had expanded their urban area. Nationwide, the total urban population, including temporary workers, grew by 20 per cent between 2010 and 2017. The area of built-up urban area, measured in square kilometres, soared by 40 per cent over the same period, according to official yearbooks of urban construction produced by the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development. “It is hard to expect local governments to set their goals in line with population shrinkage in the current economic system, under which governments still need to fight for resources to boost investment and growth,” said Xu Jianwei, senior China economist at Natixis, who suggested that a shrinking city may not be the end of the world. “It does not mean there is no opportunity for small cities that have population loss. Only after you live in a city of high density can you embrace the beauty of cities with fewer people,” Xu said. It is hard to expect local governments to set their goals in line with population shrinkage in the current economic system, under which governments still need to fight for resources to boost investment and growth. Xu Jianwei, Natixis The findings roughly correlate with a recent study by Wu Kang, a professor from the Capital University of Economics and Business in Beijing, who compared data from 2007 and 2016 and found that 11.5 per cent of cities had experienced more than three years of falling population over the course of that period. Other scholars have used different methods to estimate the scale of China’s shrinking cities, including Long Ying, a professor at Tsinghua University, who used satellite imagery to monitor the intensity of night lights in more than 3,300 cities and towns between 2013 and 2016. In 28 per cent of cases, the lights had dimmed. In the Post’s analysis of official data, more than one-third of those 71 cities still churning out new industrial zones or residential districts were located in China’s northeast. The cities are heavily concentrated in Liaoning province, an important industrial hub, which was at the heart of a data manipulation scandal in 2015 when it was reported that some local governments had inflated their fiscal revenues by as much as 23 per cent. In 2016, Liaoning reported unprecedented negative growth of 2.5 per cent. Yingkou, a port city in southern Liaoning, lost at least 100,000 people from its urban areas between 2010 and 2017, official data shows. Over the same period, its urban construction areas increased by more than 80 sq km. An official urban plan on the Yingkou government’s website, covering 2011 to 2030, estimated that the city’s population would reach two million by 2030. This is despite the fact that in the decade to 2017, it had fallen 7.7 per cent to less than one million people.

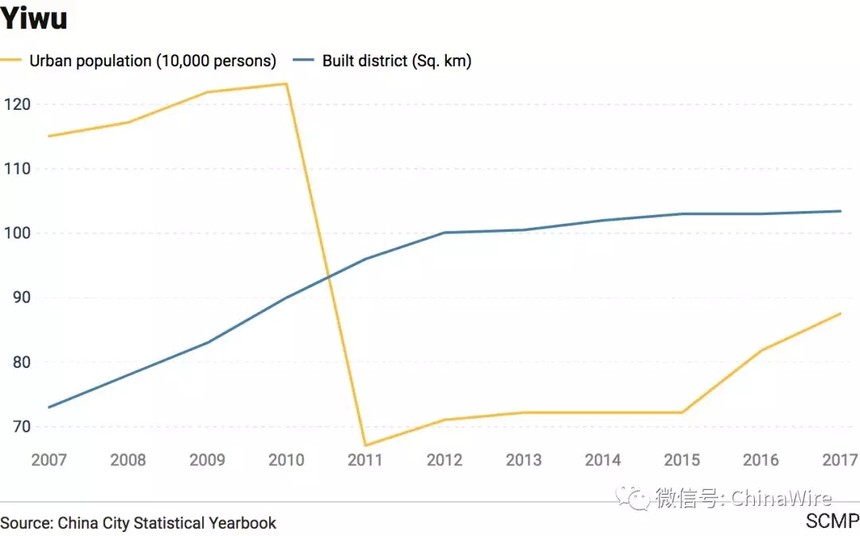

Despite a shrinking population, the city also planned to build up its urban area from 180 sq km in 2017 to 229 sq km by 2030. Dandong, located on the Yalu River that separates Liaoning province from North Korea, is the main commercial hub servicing trade between the two countries. The city’s population declined by 11,400 between 2010 and 2017, but more than 35 sq km was added to its urban area over the same period. It is not just cities in the northeast that are simultaneously shrinking and building: the problem can be found in cities throughout China’s wealthy eastern and southern provinces too. Yiwu, for instance, is a city in the central Zhejiang province, renowned for being a global marketplace for small commodities. In 2011, its urban population fell almost by half on the previous year to 670,000, mainly because many migrant workers left the city. Still, the city kept building, adding 13.4 sq km in new developments from 2010 to 2017. Fortunately for the town planners, urban population growth in Yiwu has recovered in recent years.

Most of China’s shrinking cities are relatively small, with urban populations of less than one million. However, there are few exceptions. Luoyang is one of the largest cities in the central Chinese province of Henan, with more than 2.3 million people living in its urban area. An ancient capital of China, Luoyang has been struggling to compete with the neighbouring city of Zhengzhou, the provincial capital, located 140km away, which is home to one of the world’s biggest Foxconn factories. More than 90,000 left Luoyang’s urban areas between 2010 and 2017, yet city planners added 35.8 sq km to the urban sprawl. To try to stop the haemorrhaging of its population, Luoyang is also one of China’s most aggressive cities in attempting to lure talent, offering home-buying subsidies up to one million yuan (US$149,000) per person. Not all of China’s 90 shrinking cities have kept building. Of those identified, 19 have either cut back on construction or left it unchanged. These cities include Zhang Jiagang, a port city in Jiangsu province, and Fuxin, a coal-rich city in Liaoning. Analysts have said that while China’s local governments are scrapping it out for a bigger cut of central resources, it is unlikely that this situation will change. |